In November 2017, Slovakia’s Prime Minister Robert Fico quipped that the country “must care about maintaining a friendly partnership with China, if we pay enough attention to it, we will reap fruits.” This quite illustrates the essence of Slovakia’s engagement with China during the last 15 years, when the country was governed largely by Fico (2006-2010, 2012-2018) and his successor Peter Pellegrini (2018-2020), both social democrats.

Throughout this time issues related to human rights were a foreign policy addendum at best, a useless distraction from economic cooperation at worst. Any form of dissent on part of domestic political actors was met with stern criticism. But after years of Slovakia’s ignoring human rights in its foreign policy toward China, 2020 has seen Slovakia becoming one of China’s loudest critics in Europe.

Fighting for What’s Right

In just three months, Slovak political representation objected to Chinese misinformation and mask diplomacy in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, called on China to release the Panchen Lama and other political prisoners, supported Taiwan’s accession to the World Health Organization, and decried China’s unilateral imposition of security legislation on Hong Kong.

Slovak lawmakers from both the National Council and the European Parliament were one of the largest groups in the joint statement on China’s flagrant breach of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which was initiated by Lord Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong. As of May 24 (the second day of the opening of the declaration to signatures and long before the actual adoption of the security law), Slovak politicians were the second largest group of signatories after the British. With 26 signatures at the time (now 27), including two deputy speakers of the Slovak Parliament, Slovakia was ahead of even the United States, Canada, or Australia, countries where China is a more significant political topic compared to Slovakia. Over a month later and after the actual adoption of the law, Slovak legislators still remain one of the most represented groups, despite not having any open political conflict with the Chinese government unlike many other signatories (from among European countries, Czechia and Sweden warrant special mention).

While this political activity on China in the past months was undertaken by lawmakers, the newly found courage is slowly seeping onto the executive level as well. Following the adoption of the Hong Kong national security law by Beijing, Slovakia was one of the 27 countries to sign a joint statement to the UN Human Rights Council demanding China reconsider the law’s adoption. Slovakia was the only country from the region of Central Europe to co-sign the statement.

Besides human rights issues, there is a growing recognition of security risks associated with China among Slovak policymakers. The undersecretary of the Ministry of Defense even went as far as saying in an interview that China will most likely be a subject of the country’s new Security Strategy, a brand new dimension of Slovak security policy thinking.

The Value of Non-Existent Pork Exports?

However, this has not always been the norm in the Slovak approach to China. Before 2020, China’s human rights issues were only rarely a subject of Slovak politics. Here, three events clearly stand out.

In 2009, when Chinese President Hu Jintao visited Slovakia, two crowds welcomed him in front of the Grassalkovich Palace, the seat of Slovakia’s president. A group of Slovak activists protested human rights abuses in China, especially in Tibet and the persecution of the Falun Gong. At the same time, a group of Chinese expats gathered on the square to cheer on Hu. The two groups’ meeting resulted in a violent clash; the police looked on as the Chinese diaspora members beat up the activists. In the end, the police arrested six activists and only three Hu supporters, despite both material damage and injuries to the group of activists, which included several opposition politicians as well.

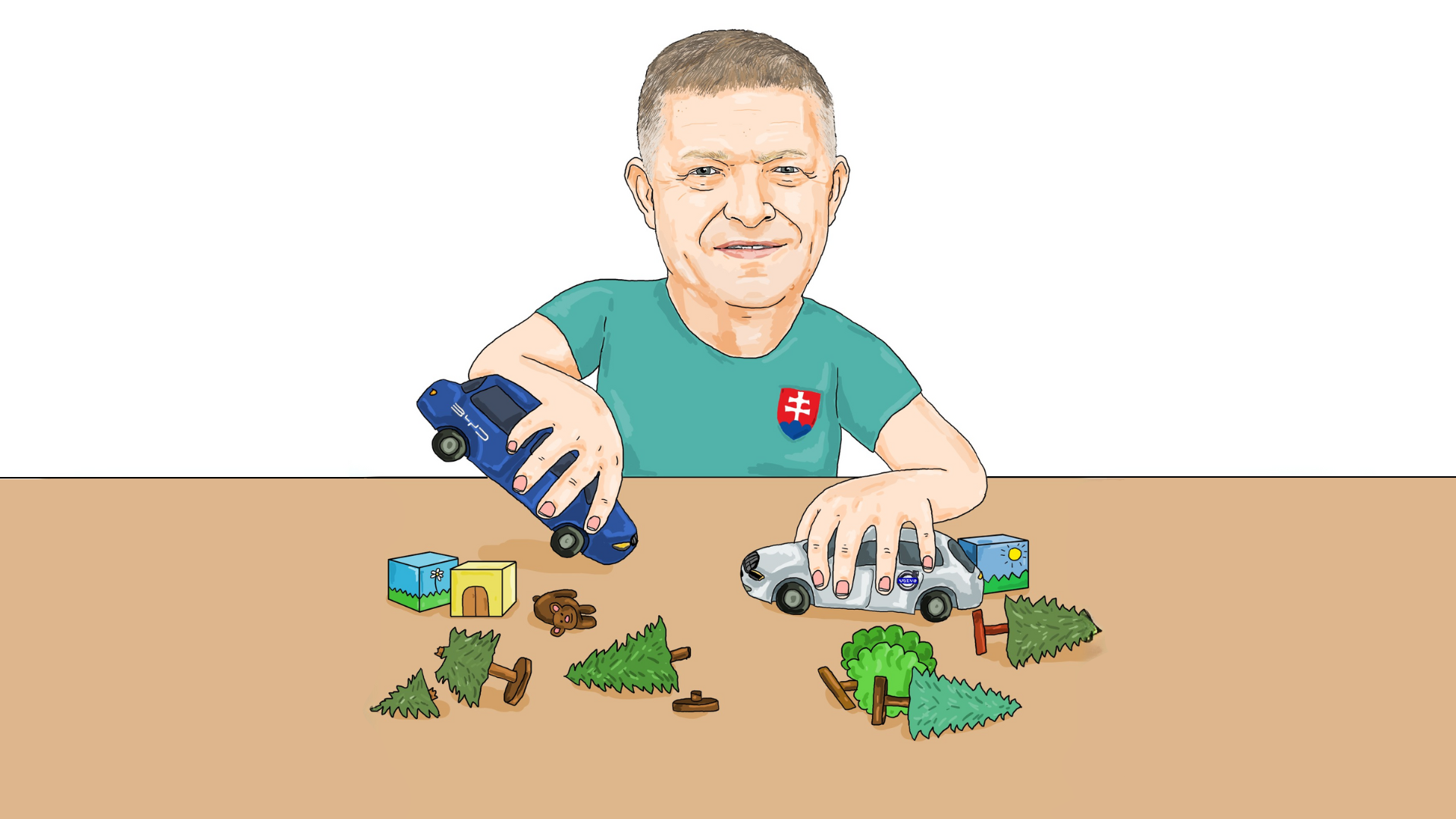

In 2016, President Andrej Kiska had a private meeting with the Dalai Lama. Naturally, this meeting was met with Chinese fury. However, Kiska drew even more anger from then-Prime Minister Fico, who turned the event into a domestic political issue when he accused Kiska of endangering Slovak economic relations with China. Fico even went as far as to claim that a potentially significant Chinese investor ceased communicating with the government as a result of Dalai Lama’s visit. Fico never provided the public with any information about this purported investor. Interestingly, after the meeting the Slovak trade position vis-à-vis China actually improved.

A similar scenario occurred in the summer of 2019, when the freshly elected President Zuzana Čaputová criticized China’s track record on human rights during a meeting with Wang Yi, the Chinese foreign minister. Čaputová was immediately berated for endangering the Slovak economy, especially agricultural exports. The cherry on the top of the absurd reaction was Speaker Andrej Danko of Slovak National Party opining that “when Matečná [the minister of agriculture at the time] calls me all scared that we are currently negotiating pork export certification and Slovakia has a negative trade balance with China, then I think that individual heroism and attacks against People’s Republic of China are not in place.” The absurdity is underlined by the fact that agriculture accounts only for a minuscule share of Slovakia’s economy and thus any exports of pork meat would have had an only negligible impact on the trade balance with China. Needless to say, the pork certification did not go through; not, however, due to Čaputová criticizing Wang, but rather because the government proved unable to prevent the spread of the African Swine Flu in the country.

These three events have a common denominator: They showcase that Slovak political leadership was willing to turn a blind eye to human rights in China — and its own values — to achieve a purportedly more favorable position for Slovak businesses.

A Lasting Policy Change?

The change toward a more values-based approach to China was facilitated by two factors – domestic political change and an external shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

On February 29, Slovakia was swept by an electoral revolution, which resulted in the unseating of the Social Democrats, who had dominated Slovak politics for almost 15 years. The government was taken over by a broad coalition of liberal, center-right, and populist parties. Research by the Central European Institute of Asian Studies, a think tank, has shown there is a clear division line on China policy between the Social Democrats (and its junior partner, the Slovak National Party) on one hand, and democratic center-right parties on the other hand. While the former can be characterized as pragmatic rent-seekers, the later put a much stronger emphasis on a value-based foreign policy.

Slovakia’s case further showcases that when it comes to the relationship between China and Europe, the discourse about China’s supposed Trojan horses in the EU is flawed, as it misses the crucial element of domestic political change and its impact on foreign policy.

China has never really been a mainstay in Slovak foreign policy. However, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated disinformation infodemic and Beijing’s propaganda campaign have brought attention to China among politicians, pundits, and even the lay public.

Thus, in less than three months, Slovakia has embarked on a collision course with China on human rights. Between Čaputová’s internationally recognized moral leadership and the emergent political consensus that China’s human rights violations cannot be met with silence, Slovakia could become one of the loudest critics of the Chinese Communist Party’s regime in Europe. Being one of the less China-dependent economies in the EU, Slovakia is well-positioned to assume the position of moral leadership.

However, for the country to achieve a long-term benefit of growing goodwill among its EU partners and NATO allies, Slovakia needs to take its newfound zeal and apply it also to the tougher security-related issues like 5G network development, Huawei market access, or general investment screening, which have so far not been high on the political agenda.

China might have been ignored until now. But the times, they are changing.