This article was originally published by TheInsider.ru

First, in late December, China and the EU unexpectedly moved to finalize a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), despite the negotiations being seemingly stuck in place just a few months before. The finalization of the deal was seen as a crucial geopolitical victory for Beijing, especially from the perspective of its long-term effort to foster division between Brussels and Washington. The calls from the upcoming Biden administration to coordinate the approach towards China and stall the finalisation of talks were left unanswered. This sent a strong message that the EU will not be adopting the US approach towards China, despite a change in the White House. Moreover, it came after a year of aggressive Chinese diplomacy towards Europe in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, which has borne the brunt of the new “wolf warrior” style of Chinese diplomats and media, including its disinformation efforts.

Yet the positive atmosphere in China-EU ties did not last long. In March, the EU moved to approve its first sanctions on China since the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989. The EU sanctions against four officials and one entity involved in abuses against Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim minorities in the Xinjiang region were met with a strong reaction. Beijing’ countersanctions targeted five MEPs, three members of national parliaments, two EU bodies, two nongovernmental institutions and also two China experts. The Chinese asymmetrical reaction, targeting those daring to speak out against China was met with a sharp rebuke in Europe. As a consequence, parties in the European Parliament have indicated they will not ratify the CAI agreement unless the sanctions are withdrawn. Now, the picture of China-EU relations seems dramatically different from just a few months before.

Now, the picture of China-EU relations seems dramatically different from just a few months before

EU’s Multitrack Diplomacy

While on the first look, this might appear to be a sudden switch in EU’s approach, it has actually epitomized the multitrack nature of EU’s China policy as well as the role of different actors influencing it. Since at least 2016, the EU has been slowly reassessing its approach towards China. In 2019, China was notoriously referred to as a “a negotiation partner, an economic competitor and a systemic rival”, a trifecta which continues to define European China policy.

Despite all the negative developments in bilateral ties with China, the focus has still remained primarily on the “partner” pillar of the trifecta. The CAI agreement was the best example of the logic that believes that China needs to be, and can be, successfully engaged in order to achieve progress in crucial areas, such as the level playing field in economy.

Such an approach has been spearheaded chiefly by France and Germany, with Merkel being the single most important champion of continued preference for increased economic cooperation with Beijing, downplaying growing tensions and disagreements in other areas, such as human rights. Merkel played a crucial role in pushing the CAI agreement past the finish line, thus achieving one of the key tasks of the German EU presidency in the second half of 2020.

Despite the public outcry towards Chinese countersanctions, which have, among others, targeted a prominent German think tank MERICS, Merkel stayed true to her time-tested China approach. In subsequent discussions with Chinese leaders, such as the trilateral France-Germany-China climate summit or the Sino-German government consultations in April, she made no mention of the sanctions issue, only broadly referring to existing disagreements and stressing the obligatory need for dialogue.

Boosting Resiliency

Yet, at the same time, the EU has long abandoned naivety in approach to China. All the while seeking mitigation of existing imbalances in bilateral relations by continued engagement, the EU has made significant progress in adopting so-called “autonomous measures”, using internal mechanisms to unilaterally address some of the outstanding issues with China.

One example of that is the investment screening mechanism, which has been approved on the EU level in 2019 and transposed into member states legislation, including an establishment of national investment screening framework. While not specifically targeting China, Beijing’s investments bonanza targeting strategic and sensitive sectors of the European economy was one of the chief motivators for the establishment of the mechanism. The latest prominent example of these powers being put to use is Italy’s blocking of a Chinese takeover bid for Italian semiconductor company.

Apart from further proposals to address the issue of subsidies that give advantage to Chinese companies in the EU market, the momentum is also increasing for tackling the issue of uneven access to public procurement market. In the EU, Chinese companies have been largely unimpeded in their access to the lucrative public procurement market for infrastructure from roads, bridges and railways to power grids. One prominent example is that of the Pelješac bridge in Croatia, where a Chinese company China Road and Bridge Corp. won the tender for the EU-funded project. At the same time, EU companies have been largely cut out from the Chinese public procurement.

Finally, the EU has been making progress in standing up for its values vis-à-vis China. In December 2020, the EU approved its Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime, which has been first put to use against China in the form of Xinjiang sanctions in March 2021. The European Parliament, and also national parliaments of member states, have been at the forefront in pushing for a value-based approach towards Beijing and pointing to the threat that China poses to European societies.

While this stress on values and willingness to confront China has only slowly affected the policies on the executive level, where “economy first” approach still reigns supreme, it is ultimately spilling over into influencing policy. On the issue of CAI, it will be the European Parliament that will need to ratify the deal together with national governments. China’s feat of antagonizing the European Parliament with countersanctions across different party groups has made this an uphill battle.

Undoubtedly, the “messy” mix of approaches across different areas of relations with China leaves a lot to desire. Moreover, the EU has been painfully slow in adjusting its approach, feeling itself unable to keep pace with the changing environment. Yet, this criticism rings true for any foreign policy issue facing the EU, with reality always falling behind the outsized expectations for the EU’s role as a geopolitical actor. Nevertheless, the EU is slowly but surely shaping a more assertive policy towards China, with the “partner” aspect of the relationship being increasingly overshadowed by competition and rivalry.

German Factor

An important milestone signaling the future development of EU’s China policy will be the September German elections. Chancellor Merkel will be stepping down, and with her the Germany’s approach towards Beijing may go as well, out of step as it is with the changing domestic views in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Importantly, the Greens, who have a good chance of forming a government after the elections, have signaled a dramatic shift in Germany’s approach towards China.

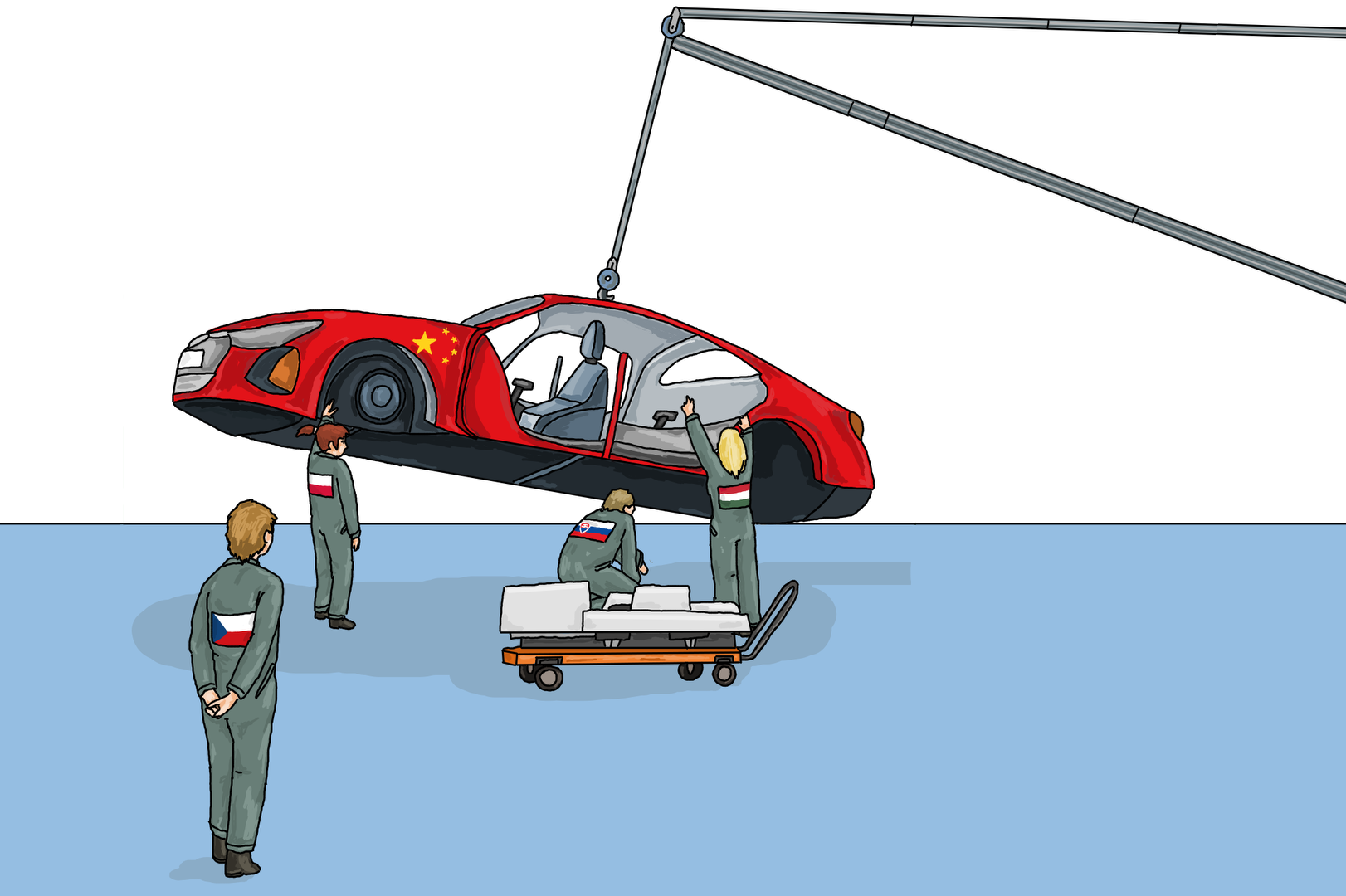

Significantly, the Greens have called for Berlin to have a China policy that would be more Europeanized. This comes at the time when several CEE countries, disappointed with the results of their ties with China within the so-called 17+1 format, are increasingly calling for a “27+1” approach towards Beijing.

While Germany has signaled its support for a common approach towards Beijing in the past, in practice it has often not hesitated to go its own way, equating interests of Germany (often, more specifically, the interests of German automakers) with European interests. Should promises be met with actions in the post-Merkel era, a gate to an even more emboldened EU China policy would be opened.