This article was originally published by CHOICE.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is forcing China into a complicated and often clumsy diplomatic dance.

China has tried to appear neutral in the conflict, for example, by abstaining in key votes on condemning the Russian aggression at the UN. Yet, it is clear from statements by Chinese officials that they are sympathetic to Russia in the conflict. China has repeatedly expressed support for Russia’s security interests, declaring that the West and the expansion of NATO are responsible for the war, having “pushed Russia to the wall.” At the same time, China vehemently rejects sanctions against Russia, even if it can be expected to adhere to them to some extent, careful of avoiding direct damage to its own interests.

Although China is, in fact, expressing support for Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as for a political solution to the situation, it does not yet appear willing to take concrete steps to facilitate such a solution beyond mealy-mouthed statements. At a time when Russia is shelling Ukrainian cities, calls for restraint on “both sides” and negotiations ring hollow, if not appearing outright absurd.

Moreover, China has also criticized Western arms supplies to Ukraine to help it defend itself against Russian aggression, claiming it also exacerbates the difficult situation. However, in practical terms, this also means robbing Ukraine of being able to withstand the full force of the Russian attack and achieving a stronger negotiation position in any ceasefire or peace talks.

The Chinese Calculus

As of late, evidence has emerged implicating China of what has long been discussed – that it may have known about the Russian invasion in advance. The United States reportedly shared intelligence with China and tried unsuccessfully to pressure Beijing to use its influence to dissuade Moscow from invading. China’s reaction was clear – it had no intention of stopping any Russian plans. According to the media reports, Chinese officials also asked their Russian counterparts to postpone the invasion until after the Beijing Olympics, not to steal China’s spotlight.

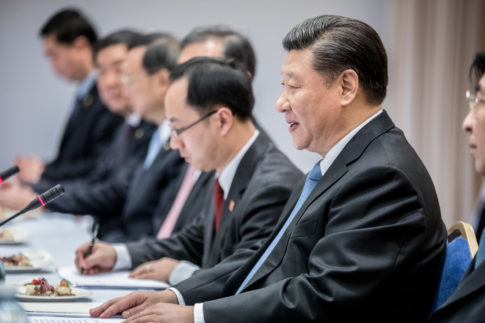

Whether or not China had specific information about the invasion plan, it can hardly be convincingly argued that China was not aware of the tense situation in Ukraine. With more than 100 thousand Russian troops already amassed the border, on the sidelines of the Olympics, Chinese leader Xi Jinping agreed in a joint statement with Vladimir Putin to support Russian strategic interests in Eastern Europe and to join Russia in the opposition to NATO expansion. It would therefore appear that, for China’s Xi Jinping, this was at least a calculated risk.

China may have based its position on two major assumptions.

First, a further deterioration of the security situation in Europe would necessitate the attention of the United States and its Western allies turning towards the old continent, hindering their Indo-Pacific ambitions. China has already benefited in the past from US involvement in the Middle East after 2001 when it was left undisturbed to focus on its own development. A pivot of attention by the United States and its Western allies to Europe, including a stronger military presence on the ground, would once again provide Beijing with the geopolitical space it needs to reap the benefits of the window of “strategic opportunity.“

Second, a deterioration in Russia’s relations with the West would force Moscow to rely even more heavily on China. Beijing has already taken advantage of this after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Now China could expect the situation to be analogous, and Russia to seek refuge in the East again, leaving China to benefit in economic cooperation but perhaps also Russia’s willingness to support China more openly on its own strategic interests.

It is too early to assess whether China has miscalculated. It is possible that Beijing was counting on a small, effective, quick, and essentially bloodless operation by Russia, as was the case in Crimea. The willingness of Ukrainians to fight might have been underestimated not just in Russia, which apparently believed it could take Ukraine without much effort.

It can also be assumed that the West’s massive and unprecedentedly united response to the Russian invasion took China by surprise, and thus also complicated its position of de facto support for Russia, which worked for China in 2014. China tends to underestimate the West and believes it faces irreversible decline. It also often highlights the incoherence of Western countries, and especially the divisions between the two sides of the Atlantic.

The astonishing swiftness of the Western response, with the EU moving to offer lethal aid to Ukraine, surprised even the Europeans themselves. In the last week, the foreign and security policies of European countries, chief among them Germany, have undergone more significant changes than in the previous few decades.

Importantly, the lesson of Russia’s expansionism may paradoxically lead Western states to start taking the Chinese challenge seriously and, in turn, increase their emphasis on security in the Indo-Pacific and plans to deter a Chinese attack on Taiwan. The hope that the West will keep itself preoccupied in Europe may thus not materialize.

However, whether today’s unity towards Russia will actually last in the long term is not a foregone conclusion. China has already had its own experience with short-lived isolation after 1989 when global outrage at the massacre of protesters was quickly replaced by the business interests of Western corporations. Current optimism about the strong Western response to the Russian aggression may thus be premature, which may also color China’s thinking. Signs of Western unity are accompanied by misguided calls for China to mediate in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, including by the EU’s chief diplomat Josep Borrell, as if Beijing could really be an honest broker.

In any case, the second assumption seems to stand – the West’s unprecedented efforts to isolate Russia seem bound to bring it into China’s arms. Moreover, Beijing can afford to ration its support as needed to avoid becoming the target of secondary sanctions. Thus, it is not advantageous for China in the current situation to publicly display its support for Russia and circumvent sanctions, throwing its neighbor an economic lifeline.

However, China will certainly look for ways to profit from Russia’s weakened position once the situation has somewhat normalized. It is, for example, not difficult to envision Chinese technology giants and their social networks playing a larger role on the Russian internet market, once Western alternatives leave Russia or are blocked there. Moscow, on the other hand, will not have much choice but to seek assistance from China and accept its conditions.

Useful Lessons

Undoubtedly, the current situation provides some very useful lessons for China.

The hefty sanctions against Russia have shown how integration into the global economy and especially the global financial system can be used as a powerful weapon. Trump’s trade war and the sanctions against Huawei have already been a warning for China. China will now have an even greater incentive to continue with its ongoing efforts to achieve self-sufficiency in key technologies and reduce the risk of dependence on global production chains.

The economic model of “dual circulation” promoted by Xi Jinping can therefore be expected to gain even more urgency. China will also undoubtedly invest more effort in the development of alternative financial infrastructure, such as the CIPS system.

Paradoxically, China may also take inspiration from the current sanctions and use them in its own foreign policy. The fact that China is not shy about using economic weapons to punish other countries has already been seen in the case of Lithuania and its relations with Taiwan. We should expect China to use coercive instruments more intensively and with greater creativity going forward.

Most immediately, the war in Ukraine has the most relevance for China’s plans for Taiwan. However, it must still be borne in mind that the geopolitical and geoeconomic position of Ukraine and Taiwan is quite different. Taiwan plays a key role in global supply chains, and in the event of a Chinese invasion, direct US involvement can be expected, unlike in Ukraine. In addition – and this may sound trivial, but it is a key factor – Taiwan is an island 150 kilometers from the Chinese mainland, which presents a radically different military challenge.

Given the enormous shocks to the Russian economy and the (as yet uncertain) potential to destabilize the Putin regime, it seems unlikely that the current situation will strengthen Beijing’s will to use the military option against Taiwan. On the contrary, the immediate risk of war may decline.

This autumn, the Communist Party faces a crucial 20th Congress, which is expected to confirm Xi Jinping’s continuation as a party leader. A destabilizing conflict is therefore not in the interests of the Chinese leadership.

However, China will undoubtedly monitor the current situation and use it to prepare for any future conflict over Taiwan and brace itself for the anticipated Western response.