This article was originally published by CHOICE.

On the sidelines of the Beijing Olympics, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met for the 38th time, issuing a joint statement that may well become a major milestone in bilateral ties.

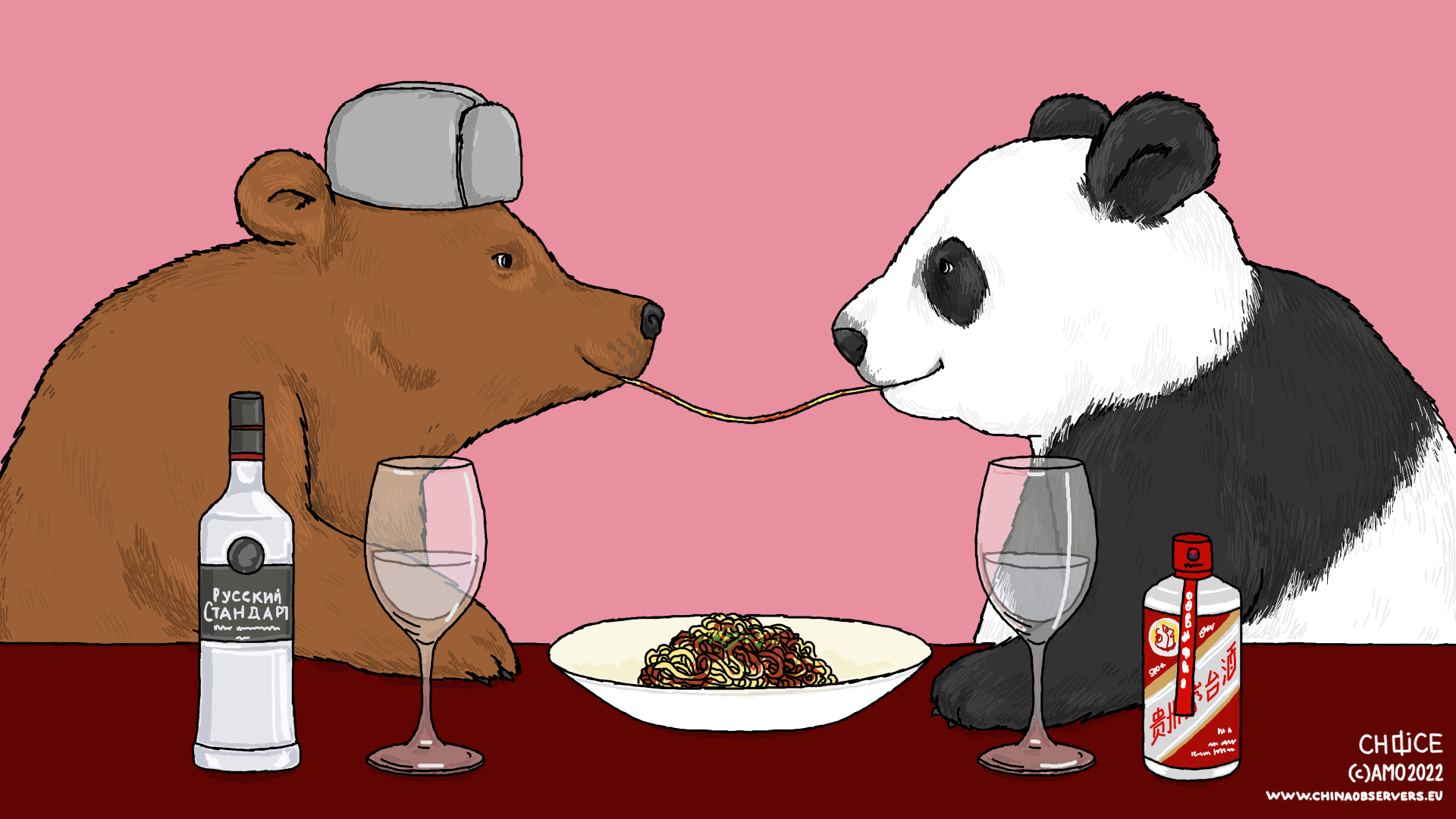

The document underlined the ever-closer relationship between the two powers, united by their joint opposition to the US-led Western liberal order. Long dismissed as a marriage of convenience, the latest statement suggests it would be a mistake to downplay the ability of the two powers to present a united front and openly assist each other on key interests.

The document explicitly outlined shared perceptions of new enemies – be that NATO from the Russian view, or AUKUS from the Chinese perspective – and brought to the world’s attention the degree to which both actors are willing to cooperate on issues of common interest.

Russian Perspective

For Russia, the partnership with China is beneficial on several levels.

First of all, China finds itself struggling against the established world order and seeks to rewrite the rules of the game in security, as well as in the economic and political architecture of the world. Meanwhile, Russia increasingly isolates itself by way of its aggressive stance in Eastern Europe, making breathing space on the international level increasingly important to find as it struggles against the same constraints.

It is no coincidence then, that the first point of the joint statement revolves around Sino-Russian opposition to the Western “monopolization” of the term democracy. Not measuring up to that definition, Russia and China have been cast as international pariahs, most lately at the December “Summit of Democracies” organized by Washington. Therefore, the two powers are setting about to shift the definition of the term and legitimizing their own regimes under their own definitions and norms rather than the West’s.

The current status of the bilateral relationship has its roots in the post-Crimea developments, which effectively isolated Moscow and caused its attention to orient more intensely toward Beijing. The previous competition between the two powers was, to some degree, replaced by the need for partnership and pragmatic cooperation against a common enemy in the US-led West. For Russia’s active attempt to restore its own perceived sphere of influence by force, China was an ideal ally in countering the so-called color revolutions in its backyard, from Kazakhstan to Belarus.

At present, Ukraine plays an integral role in Moscow’s calculus. But without China’s help, it seems impossible for Russia to challenge Ukraine backed by the West and withstand the brunt of sanctions. This is why Putin’s trip to Beijing can also be interpreted as effectively asking for a blessing to escalate the situation further.

The blessing is crucial as a growing asymmetry emerges between both players in which Russia cedes economic ground to China, but Russia nonetheless remains economically dependent on energy exports, mostly to the West.

At the same time, it is evident that Russia’s endorsement of Chinese opposition against AUKUS in the joint statement is purely pragmatic and reciprocal in nature. The statement also expressed joint opposition to NATO’s enlargement in Eastern Europe. Still, China did not reciprocate on the issue of Crimea, which Russia could have demanded upon endorsing the Chinese position on Taiwan, although this has been a longstanding policy. In any case, both actors might celebrate a victory, one that did not come at significant cost or entanglement.

China Drops Cautious Approach to European Security

From China’s perspective, the Sino-Russian statement holds importance as a precedent setter.

China made an explicit statement against NATO’s expansion and supported Russia’s quest for security guarantees, endorsing a de facto rebuilding of the current European security order.

China was for a long time extremely wary of involving itself in European security issues, presenting itself instead as a purely economic actor. This often put China into an advantageous position. For example, China was not-too-long ago presented as a potential way to cushion the loss of the Russian market after post-Crimea sanctions and agriculture trade embargo in Poland or Lithuania. Likewise, economic opportunities from China partly counterbalanced the loss of Russia’s market for Ukraine, with the Asian power becoming Ukraine’s largest trade partner in 2019.

At the same time, China benefited from Russia’s isolation and need for China’s support post-Crimea. This reliance manifested itself, for example, in the Russian willingness to sell China advanced weapons it was not willing to part with before.

Still, the question of why explicit endorsement was forwarded at this moment is worth considering.

It is clear that China has long respected Russia’s perceived sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. The view that great powers have certain legitimate core interests that must be respected is deeply ingrained in China’s view of international relations. The omission of Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova into its 16+1 cooperation format is very much understandable under this consideration.

China’s opposition to NATO is not surprising either.

Beijing has long decried military alliances of any kind, casting them as outdated remnants of the Cold War era. Yet, while China has sought to undermine US alliances in Asia, NATO until recently figured very little in Chinese strategic thinking, for the simple reason of geography. Beijing has never made explicit its opposition to further enlargement of NATO.

Yet, put bluntly, it might now be the impression in Beijing that there is nothing left to lose by taking Russia’s side.

In recent years, NATO has already started to turn its attention to China, identifying it as a key challenge in the future despite China’s silence on the alliance itself. Additionally, China’s ties with the EU countries have been at their worst level ever in the past few years, with China making it clear that it is willing to sacrifice ties as it did in the CAI (Comprehensive Agreement on Investments) and sanctions drama of 2021. In short, Beijing may no longer see maintaining its careful stance on European security as crucial to its interests given its chilly reception on the continent already. Finally, supporting Russia on the question of NATO is ultimately a rhetorical move, which does not require China to make any meaningful commitments.

However, by clearly taking Russia’s side on the issue of the security architecture of Europe, China is taking significant risks.

The move may further alienate European countries, especially those in Central and Eastern Europe, that see Russia as a primary security threat. Both within this region and beyond, the notion that China and Russia are representatives of a two-headed monster of authoritarianism, that needs to be countered with vigor, will gain serious supporting evidence.

China’s coming out may also put an end to delusions about the use of China as some kind of balancing power against Russia in Europe. The absurdity of the notion was laid bare when the office of the Polish President Andrzej Duda explained his trip to Beijing as a chance to provide a “European perspective on the situation” in Ukraine to Xi Jinping.

What’s Next for Sino-Russian Ties

As the joint statement suggests, pragmatic cooperation between the two powers is entering a new era.

Russia desperately needs an international partner in a situation of growing isolation from the West, which might further deteriorate in case of the potential attack against Ukraine. Meanwhile, China similarly appreciates a like-minded revisionist power endorsing its vision for the Indo-Pacific, especially since Russia is not threatening its direct interests and goals in the region.

Furthermore, bogging US attention down due to Russian military threats has significant strategic advantages for China, namely in thwarting Washington’s efforts to pivot attention to the Indo-Pacific. In any case, the virtual non-aggression pact between the two countries frees their hands significantly to focus on other challenges. This is shown by Russia being comfortable enough to shift its military forces from the Eastern theater to bolster its ongoing force buildup at the Ukraine border.

At the same time, it is right to remain mindful of potential limits and barriers to a closer bilateral relationship.

Due to the declining power of Russia – most notably on economic grounds – further isolation from the West might lead to increasing dependency on China. In this dynamic, China is hungry for more energy resources as well as other natural resources from Russia. Thus, the future effective subordination of Russia to China is still likely to provoke conflicts.

One concrete trace of it was already evident during negotiations over natural gas, from which China emerged as the winner by receiving a relatively low price, especially when compared with the EU countries. At the same time, Beijing is carefully balancing the Russian imports by cooperating with the Central Asian countries as well as Myanmar in order to keep Russia at bay, especially when it comes to pricing.

Most immediately, the issue deserving attention is Ukraine. China has always walked a tight-rope in the issue, evident in its reaction to the annexation of Crimea. China abstained in the crucial UN Security Council votes on Crimea, but it never officially accepted the annexation. Since, Ukraine has become an important partner for China and remains a key transportation hub for interconnectivity plans with the EU.

In case Putin decides to attack Ukraine, China would most likely remain on the sidelines, trying to avoid entanglement. Even if any instability caused by the attack would not be in China’s interest, China is unlikely to attempt to dissuade Russia from invading. In the aftermath of a conflict, Beijing would again shield Russia in the UN and provide it with effective support in face of international sanctions. This, in turn, would increase the Russian dependency on China at multiple levels. The West’s reaction will also be gauged in Beijing in light of its own designs in the Taiwan Strait, even if China is highly unlikely to subordinate its ‘reunification’ timetable to Russian plans.

Still, it seems that the best scenario for China is for the current impasse to continue, tying down the US and West. Whether the situation develops in any direction, Russian dependency on China is only set to increase. China, on the other hand, is likely to emerge from the crisis with a bolstered geopolitical position, no matter the result.