Hungarian Media Analysis

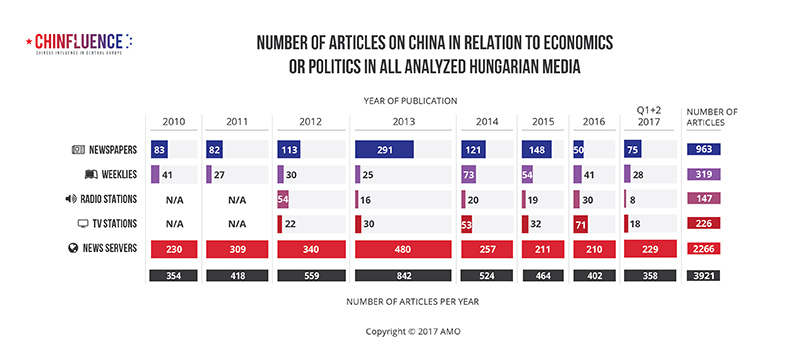

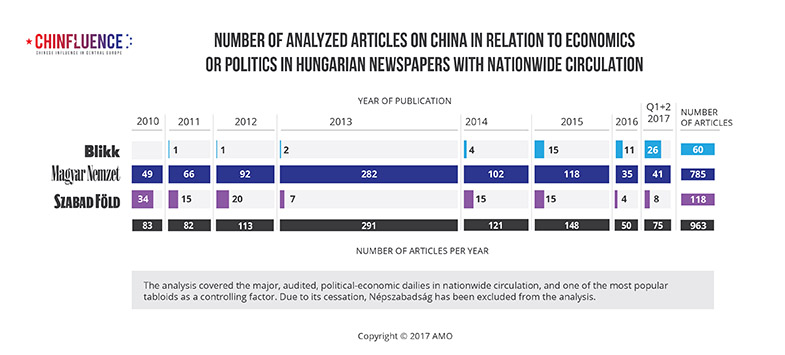

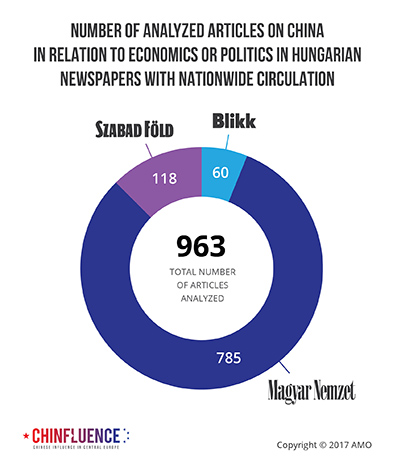

Altogether, the Hungarian part of the project subjected to an analysis 3921 Hungarian media outputs, published between 2010 and June 2017, on China in connection to economic and/or political issues. For the analysis, we selected 15 media sources which were most widely read, listened to or followed and had a nationwide coverage – dailies, weeklies with a political or economic focus, radio and TV stations and news servers. We analyzed both mainstream media and tabloids, those that are public as well as privately owned.

For the results of the analysis, please check the following infographics.

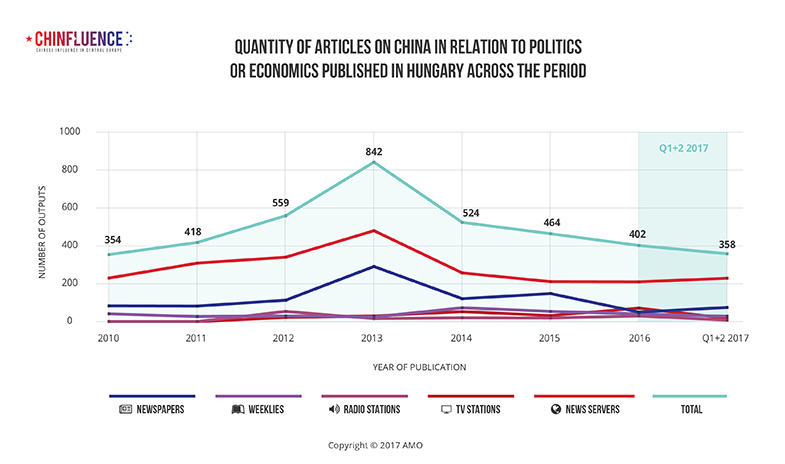

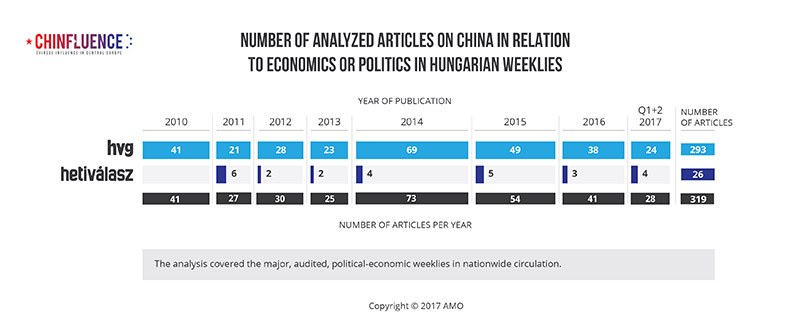

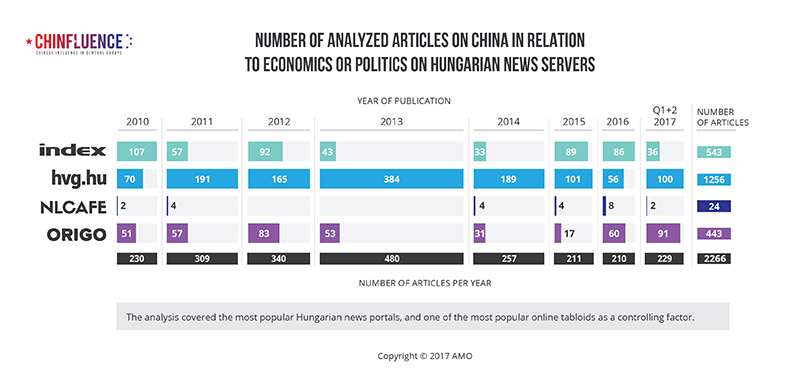

The first finding reveals that the number of articles on China have been relatively stable in the analyzed period. The only exception was in 2013, when the gathering of the National People’s Congress and the inauguration of the new Chinese government resulted in a spike of published articles.

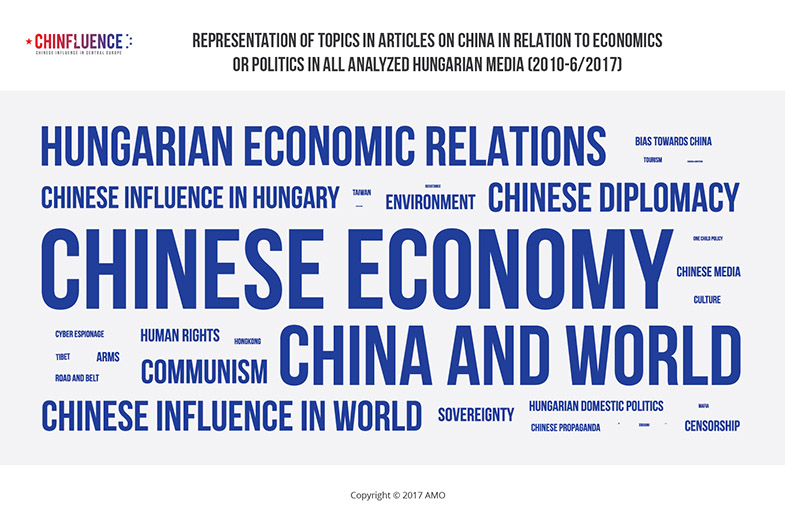

The majority of almost 4000 articles we analyzed focused on the general economic situation of China, its role in world politics and economics and the development of Hungarian-Chinese relations. Meanwhile topics like human rights, Tibet or the protection of intellectual property rights have been barely mentioned.

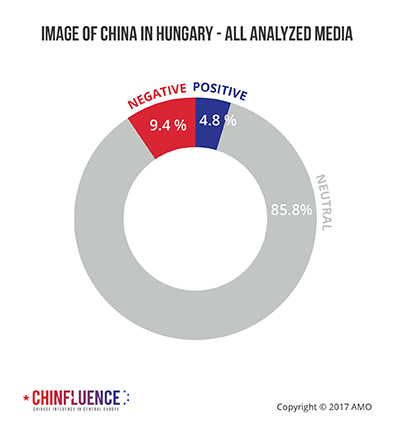

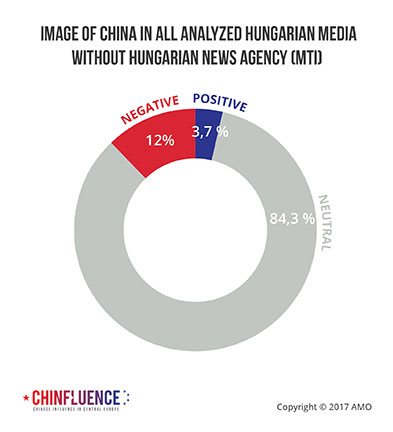

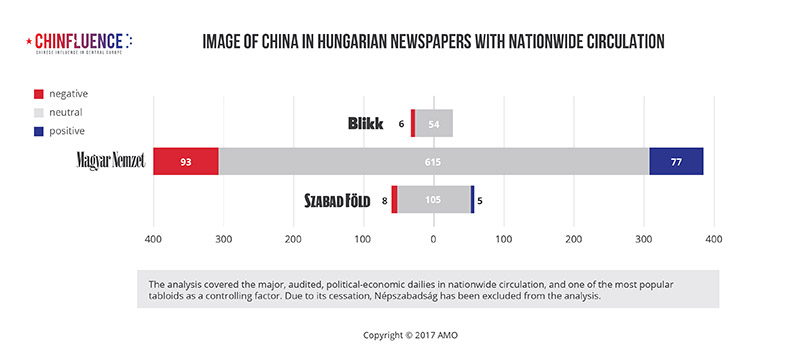

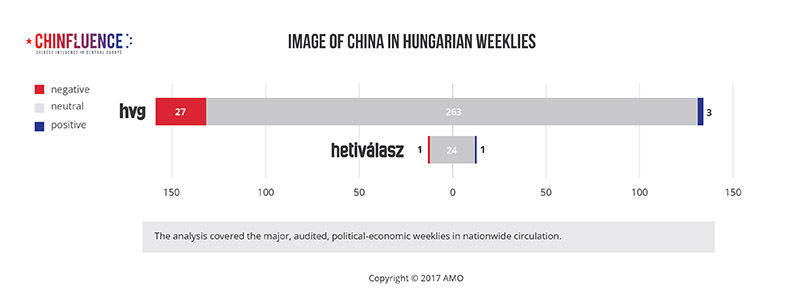

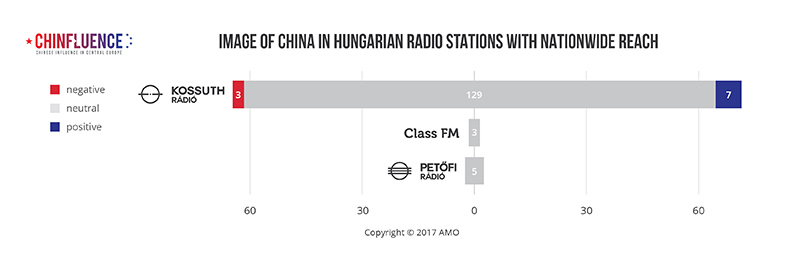

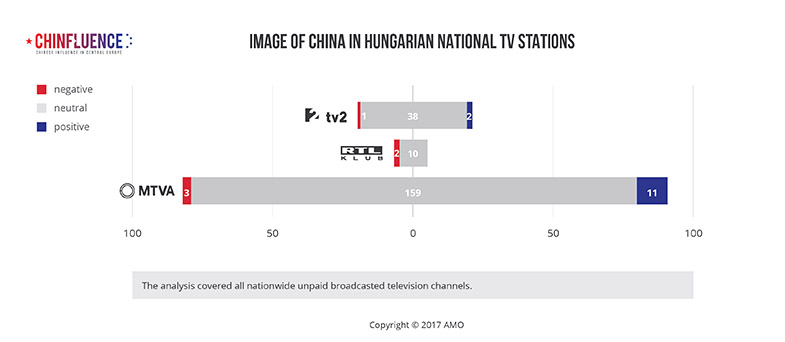

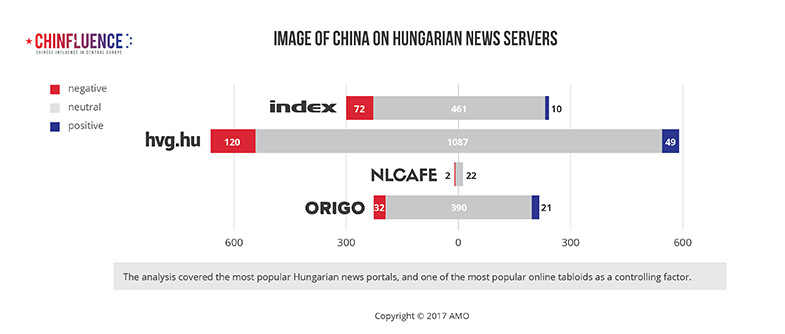

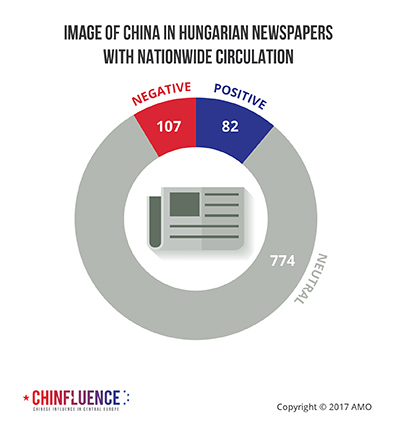

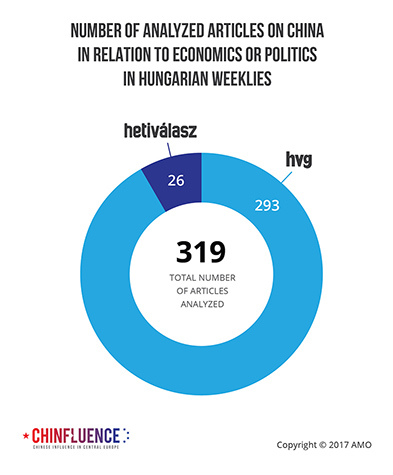

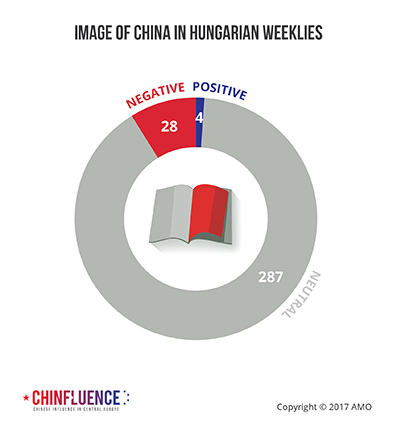

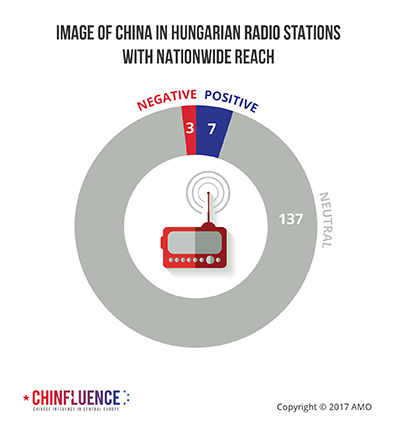

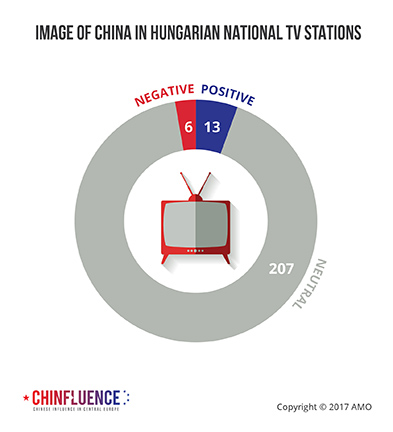

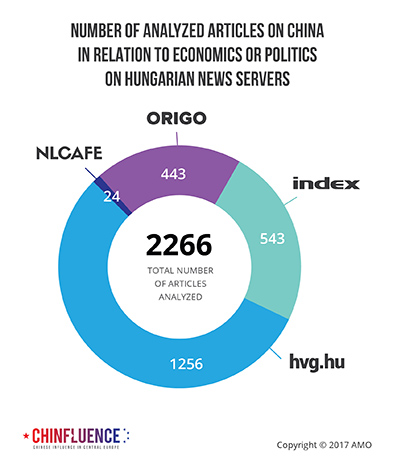

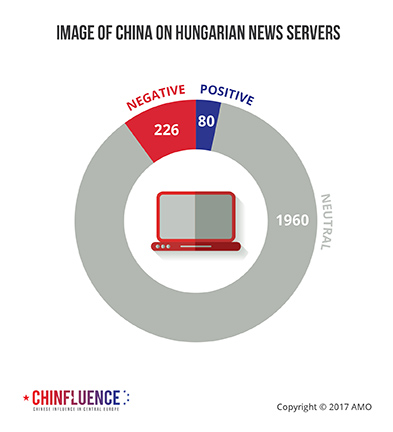

It is noteworthy that more than half of the articles were published by the small group of online news services. Thus, hvg.hu alone published almost one third of all the articles, while index.hu and origo.hu are responsible for 14 and 11 percent respectively. It also has to be mentioned, however, that the original source of at least 52 percent of all news was the official Hungarian news agency (MTI) thus the share of articles produced by other media outlets themselves was less than half of the total. This fact has had an impact on the generally neutral image of China in the Hungarian media, as 87 percent of the news based on the MTI as a source were neutral. Including all sources, it seems that 4.8 percent of news were positive, 9.4 percent negative and 85.8 percent neutral between 2010 and 2017. When excluding all news based on the MTI, the picture gets slightly different: 3.7 percent of the articles produced by media sources themselves was positive, while 12 percent was negative. Still, the overwhelming majority of reports was neutral.

In order to shed more light on the details of the Hungarian media discourse, the methodology could be slightly altered to reshuffle results. When the categories of negative/positive articles include not only publications which deliberately intend to influence readers/viewers/listeners into a negative/positive direction, but also publications simply conveying good/bad news in a neutral wording, the picture gets different. This approach is based on the assumption that even balanced news services may influence the audience by selecting between good or bad news. By applying this method we found that news published by MTI were by 37.7 percent neutral, 28.3 percent good news and 34 bad news. Meanwhile other players of the news market broadcasted only 23.6 percent good and 38.7 percent bad news, and 37.7 percent neutral ones. This means that the publications produced by the media sources themselves are significantly more polarized and negative, than one might have thought based on the initial data.

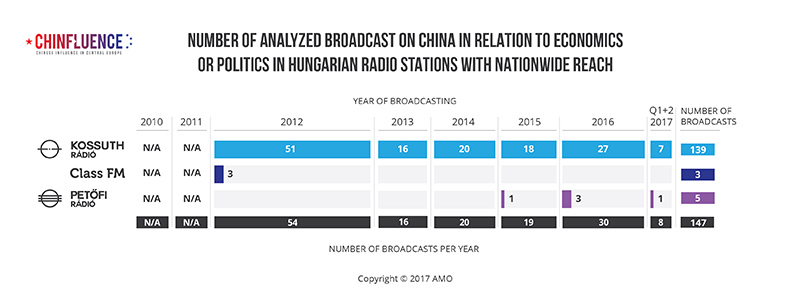

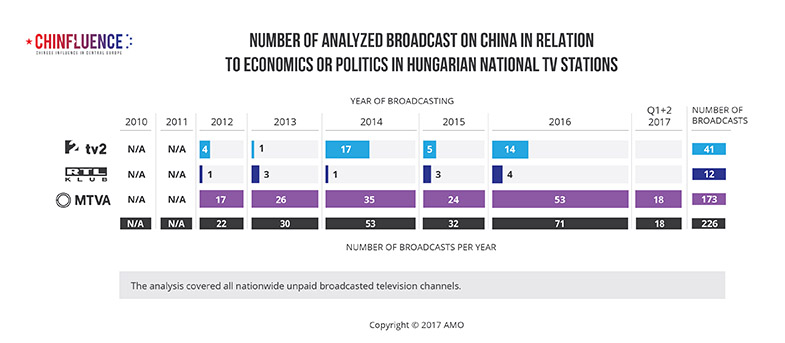

Taking individual media sources into account it is obvious that domestic political division lines have an impact on the image of China itself. Media sources believed to be close to the government (Hungarian national television and radio channels, TV2, origo.hu) publish significantly more positive and good news about China, while media sources on the opposition side (Magyar Nemzet daily, index.hu, HVG, hvg.hu, RTL Klub) published many more negative or bad news than positive ones. Still, neutral news dominated their activities.

Dedicated sections above provide detailed insight into the situation in specific types of media.

Aforementioned findings do not question the objectivity of the reporting concerning China – the project did not verify the validity of the information, only assessed whether the message, vis-a-vis China, was neutral, negative or positive.

In contrast with the situation in the Czech Republic, in Hungary the share of negative news (thus the polarity of the discourse on China) had been constantly increasing during the period in vogue. In 2010 negative news made up 6 percent and positive news 5 percent of all articles. Meanwhile, the share of negative news rose to 15 percent against 5 percent of good news in 2017. The year of 2013 seems to be the turning point, since there were 4 percent positive and 3 percent negative in 2012, and as high as 12 percent of all news on China were negative and 5 percent positive in 2013.

The graph presenting the most frequently mentioned topics draws a clear picture of the media discourse on China in Hungary. Compared to the Czech results, Hungarian discourse is materialistic with articles mostly focusing on economic and business cooperation (the performance of China and its global influence were the most common topics od the texts). Meanwhile, values and principles (like Tibet, Taiwan, authoritarian nature of China’s regime, human rights, censorship etc.) have had a minimal presence in the Hungarian discourse, what is in the stark contrast with the Czech case.

To sum it up, the Hungarian media discourse on China is one sided, focuses overwhelmingly on pure economic data and developments on the one hand, while it is strongly politicized on the other. The assessment of Hungarian-Chinese relations in the media is strongly influenced by the political attitude of the given media source towards the government. Consequently, a productive and useful discourse on China and on bilateral relations has never evolved in Hungary, and the public sentiment is mostly influenced by a handful of agenda setters (see the network analysis), whom are mostly politicians and not experts of the matter.

It is also noteworthy that in comparison with Czech data the Hungarian media discourse is a way more materialist, focuses merely on economics and potential financial opportunities and risks, while topics like political values, human rights, minorities or democracy are almost completely missing from the agenda.

Hereby we would like to express our appreciation to the following students of the Corvinus University of Budapest who contributed to the research: Adouki Flóra Anna, Aranyossy Márton, Bakos Dóra, Beregszászi Balázs, Berendi Barbara, Czárth Luca Kata, Engelbrecht Azurea, Flaskár Dóra, Ford Oliver James, Kotzmanek Roland, Kovács István Márk, Tóth Patrícia, Lakatos Levente, Lakatos Zsófia, Liszka János Attila, Major Balázs, Móra Dominik Attila, Németh Gergely, Savci Armanda Leila, Szabó Bálint, Taraczközi Anna, Tóth Patrícia, Tőke Tímea.