Ivana Karásková was one of experts asked to comment on the impact of the coronavirus epidemic on China-EU Relations. All the responses can be seen at the China File website.

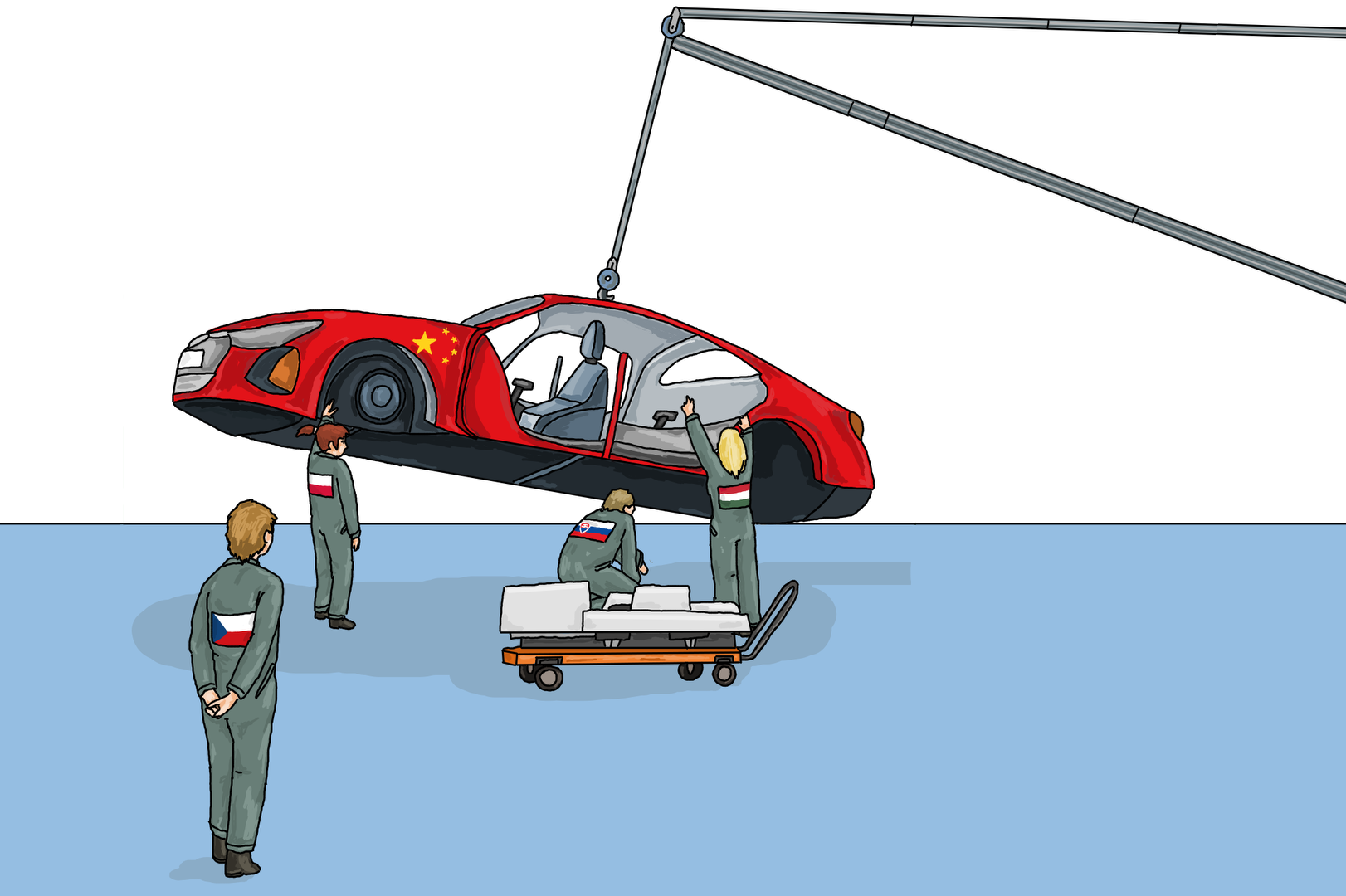

During the global financial crisis, China largely shed its image as a developing country ruled by an odious regime. The crisis offered China a way out of ideological ostracization, inflated both its economic clout and soft power, and brought its influence to regions where it had never before existed, such as Central Europe. China ceased to be regarded as the world’s factory, and for some countries became instead a creditor of the last resort.

Today, the situation is both similar and substantially different. China continues to play a key role in the international economy—now far more developed and sophisticated than during the previous global crisis. It is also a substantially more self-confident player. With countries scrambling for medical equipment, while the U.S. flounders thanks to an erratic and self-absorbed lead, Beijing is trying, once again, to play the role of global savior.

Yet, much is different. With its growing power, China has faced predictable opposition. Its strategic ambitions have provoked the U.S. to adopt a balancing act in the Asia Pacific, while across the Western world, Chinese actions and actors have become a diplomatic irritant—as demonstrated by European and American reactions to Huawei. Also, notwithstanding the ugliness of Donald Trump’s discourse about a “Chinese virus,” the outbreak of COVID-19 did in fact originate in China—and the country’s initially incompetent reaction allowed its spread. While in relation to the global financial crisis Beijing could legitimately claim it was offering a solution, this time it is undeniably a part of the problem.

All of this will shape the future of EU-China relations. However, much will depend on the situation within the EU itself. First, the speed and scope of economic recovery will be crucial. Second, Europe will only be able to recover fully if it rediscovers its solidarity. Without substantial EU-wide transfers, some regions (particularly northern Italy) will not be able to overcome the damage caused by the pandemic. Third, even if efficiently deployed, intra-EU solidarity will come to naught if Europeans don’t internalize it. So far, European institutions and member states have done an extraordinarily poor job pointing out the benefits of cooperation.

If Europe pulls its act together and the EU’s success is sold to the Europeans through an effective communications strategy, EU-China relations will be minimally affected.

The worst-case scenario could become true if Italy is allowed to fall, thus becoming a nightmarish “second Greece.” There, China leased the port of Piraeus; in post-COVID-19 Italy, it could buy the whole country. In some countries, Chinese “help” (often bought in hard cash) is already greeted with devotional reverence. Through their indolence, member states and EU institutions could increase the space for China’s influence. This process would not, of course, go unopposed, but it is not beyond imagining. The result could be an EU torn into pieces along yet another dividing line. As usual, the solution is largely in the Europeans’ own hands.