Over the past decade, geopolitical and geo-economic centers of gravity have been gradually shifting eastwards, away from the Transatlantic area towards the Indo-Pacific. The events of the past year and a half have demonstrated rather well what this process entails. Not only is the US increasingly active in the Indo-Pacific and paying less attention to what is happening in the EU’s neighborhood, but we have also seen the full extent of Europe’s dependence on East Asian markets and Indo-Pacific sea lines of communication.

Even in countries like Slovakia, which have never paid that much attention to East Asia, any serious conversation about foreign policy hardly goes by without at least a fleeting reference to China and the broader Indo-Pacific region. These conversations are largely overdue, as Central Europe has already benefited greatly from economic interactions with the region, with South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan being important sources of FDI for the Central European economies.

However, it is not enough for the Central Europeans to pay attention only to the particulars of the bilateral exchange. In an interdependent world, Central Europe needs to be part of the broader discussions about security in the Indo-Pacific. While largely undervalued, if conflicts in flashpoints like Taiwan Straits or the South China Sea were to erupt, Central Europe would not remain unaffected. As a 2016 study by CSIS reveals, Central and Eastern European countries transport as much as 5 to 10 percent of their overall trade via the South China Sea. A conflict disrupting the world’s busiest trade route would have a large-scale impact even on most areas of the world, Central and Eastern Europe included.

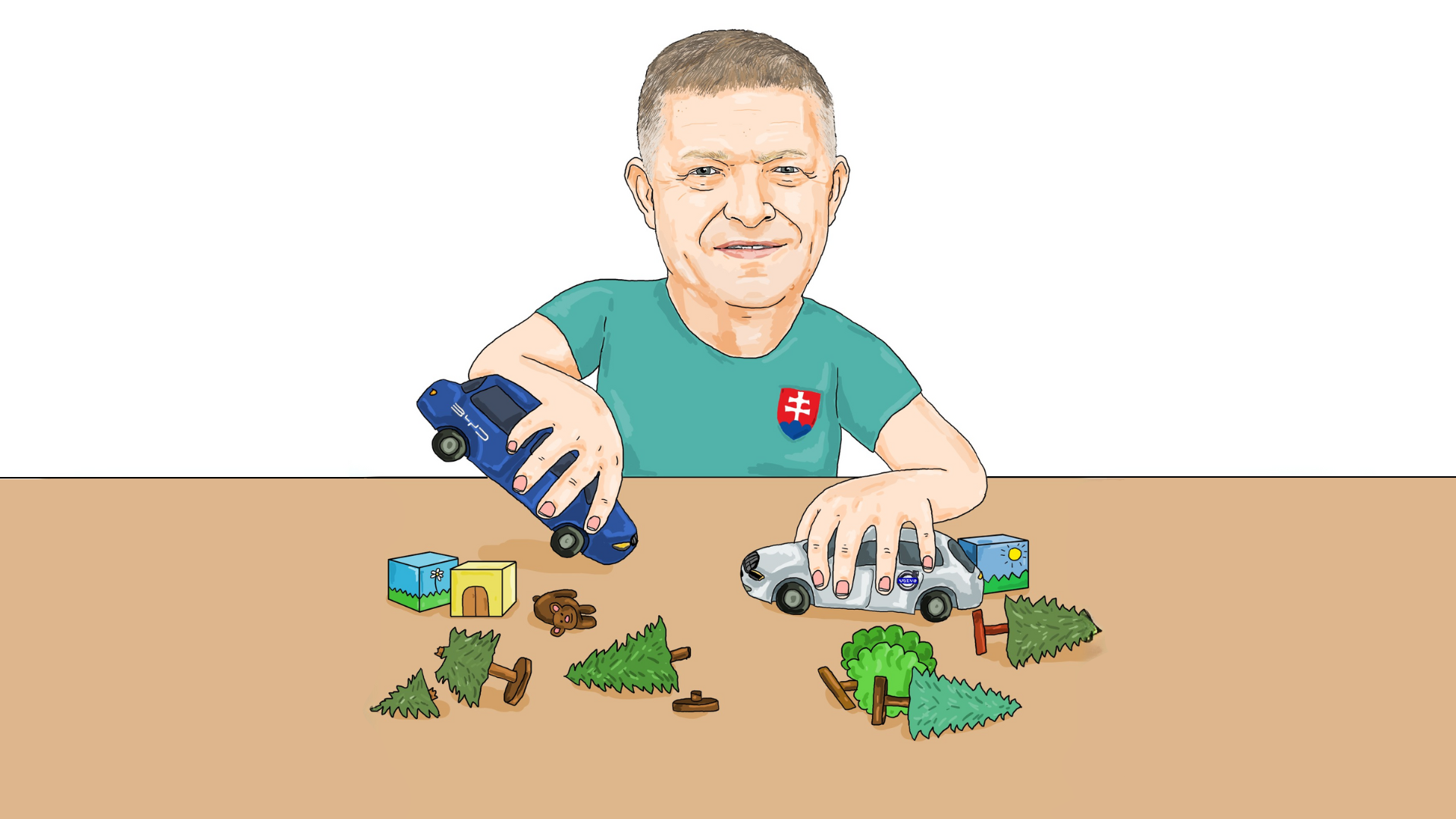

The region has already felt the potential of this impact over disrupted semiconductor imports due to COVID-19. Regional economies dependent on the car industry (Slovakia, Czechia, etc.) have seen repeated operation interruptions as their just-in-time production models were incapable to deal with the lack of semiconductors. Certain auto-makers had even announced mass lay-offs as a result.

Nevertheless, when it comes to East Asia, most CEE countries are faced with significant obstacles such as power asymmetry, scarcity of resources, and lack of qualified personnel. Neither of these obstacles has a short-term solution. Thus, if the CEE countries wish to be successful actors in the Indo-Pacific region, they are destined for mutual cooperation. In this regard, the EU provides them with a natural step-ladder to overcome some of these hurdles, especially the hurdle of power asymmetry. Due to this, CEE countries will need to realize that a key to successful engagement with the Indo-Pacific lies not only in their own capital and capitals of their East Asian partners but equally so in Brussels. To deal with the scarcity of material and human resources, other modes of cooperation may be also useful. The V4 countries have already rather successfully utilized the V4+ format to foster ties with Japan and South Korea. The platform may prove useful in fostering people-to-people relations, promoting cultural diplomacy, and pooling development aid resources. Here, cooperation seems the most viable as, unlike in economic diplomacy, zero-sum games hardly occur.