Czech Parliamentary Discourse Analysis

The policy paper is available for download here.

ChinfluenCE subjected to an analysis 558 transcripts of plenary sessions at Czech Parliament held between 1993 and the very end of the year 2018. Out of those, 441 were plenary sessions at the Chamber of Deputies and 117 sessions of the Senate. Out of all the available documents only direct transcripts of plenary sessions were selected as they most accurately reflect not only debated topics, but also sentiments towards China expressed within individual speeches (neutral, negative, or positive) and keywords used during the debates on the parliamentary floor. Data within all of these categories were carefully measured, analyzed and put together to reflect the Czech parliamentary discourse.

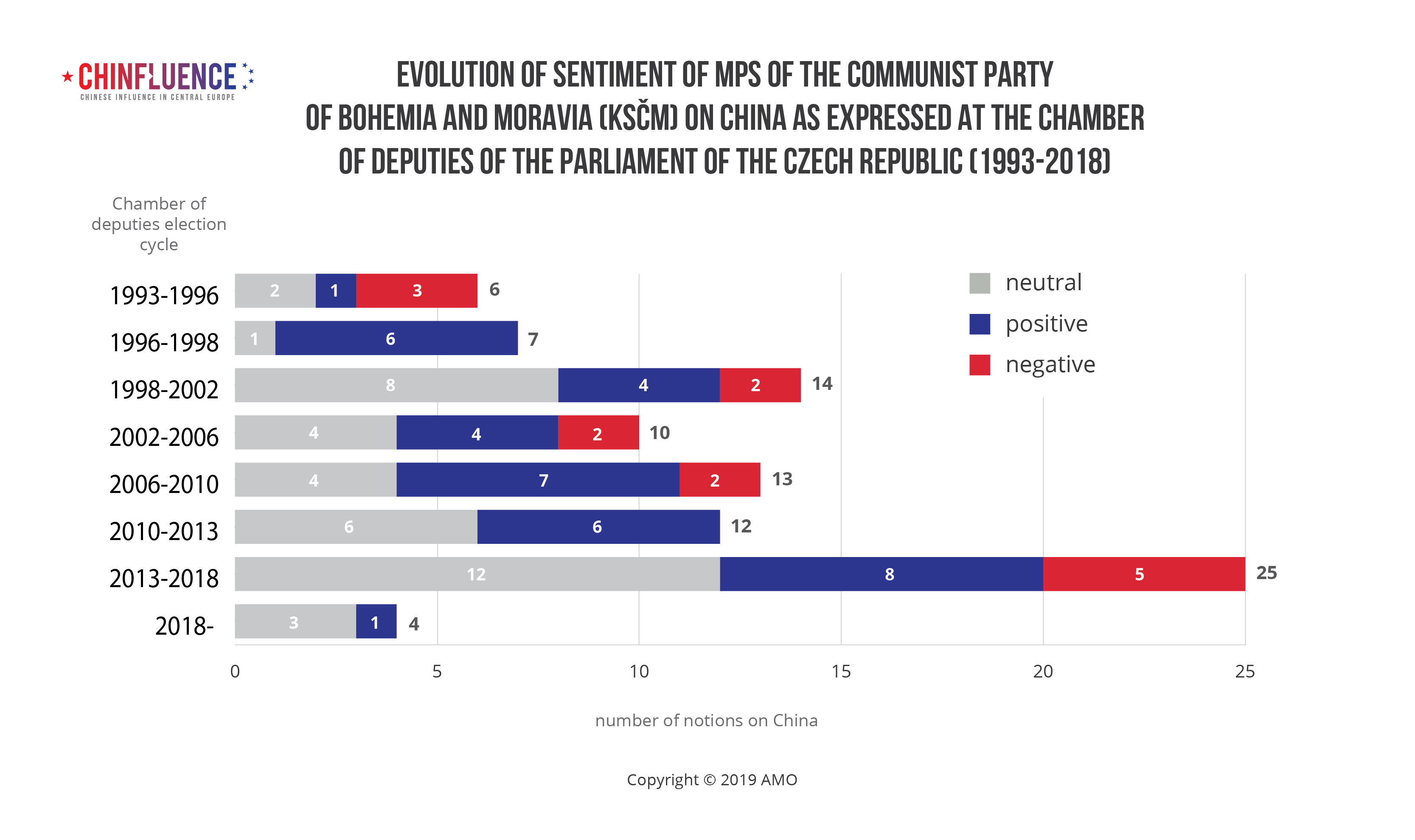

Until recently, mentions of China represented a marginal component of wider political debates in the Czech Parliament. The Czech debate on China was seemingly negative from the very beginning of 1990’s, however, nearly the entire dataset from the early years was formed just by brief mentions of China, or by using in as an example. An actual debate on China formed in the Czech Parliament only after Beijing’s newfound interest in the CEE region in 2012 and 2013.

What followed was a Czech-China honeymoon period filled with friendly discourse of present and planned achievements. Simultaneously, China was criticized by the opposition due to a new set of issues that came along with the intensified contact. As the economic dream failed to come true, the defending voices went rather silent or limited themselves to references to the current state of affairs, and the criticism towards China prevailed.

As in case of the media analysis conducted before, the number of debates where China was mentioned rose dramatically with the intensification of the Czech-Chinese bilateral political relations. The strongest moment of that period was the official state visit of the PRC’s President Xi Jinping to Prague in 2016.

The policy paper is available for download here.

While positive notions of Beijing fluctuate wildly from an almost negligible share to more than a third of utterances, the negative views have been held in a more constant manner. This is in stark contrast with the results of the Hungarian parliamentary discourse mapping . Interestingly, with strengthening the political ties with China, animosity of Czech politicians towards the country rose dramatically at the parliamentary floor. That is in direct contrast with the Czech Foreign Policy towards China, which was the friendliest in history during the same time period. In sum, despite repeated efforts to promote more friendly Czech-China relations, there has always been an irrepressible opposition to this tendency in the Czech Parliament.

In the past 28 years, we found 125 China-related topics. Those were created by condensing thematically related individual keywords identified in the MP’s speeches. The results show that the Czech parliamentary debate is heavily influenced by and linked to Czech internal politics, and that the economic concerns play as much of a strong role as the issue of human rights. China is also frequently – although mostly briefly – mentioned in a context of geopolitics as an influential player.

China-related debate on the Senate floor were tied to the Czech internal politics as well and even more linked to the issue of human rights.

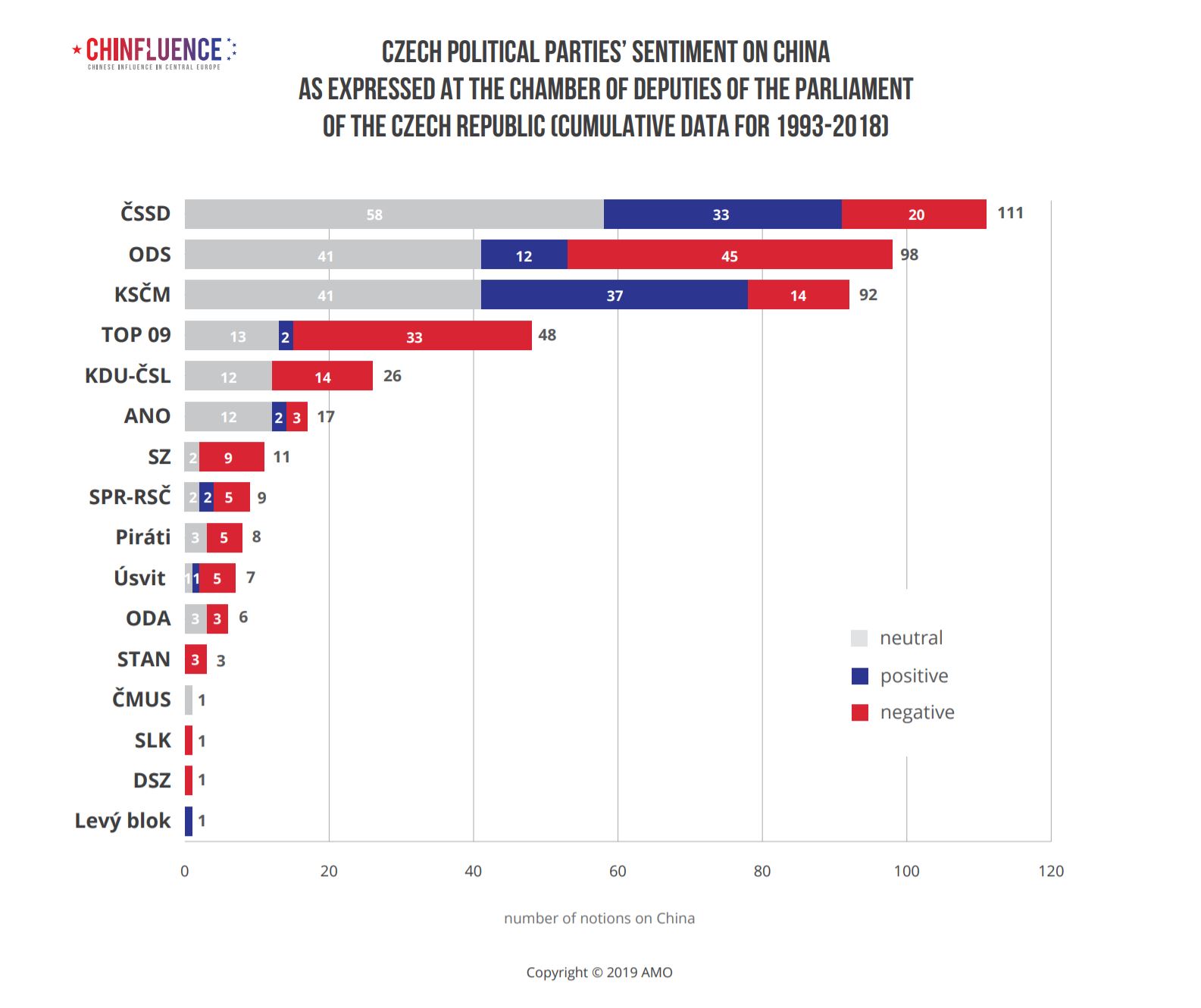

Research on Czech MPs’ views and political parties’ views on China revealed that their sentiment varied from slightly positive towards generally forthcoming. Positive representations of China have been closely tied to the logic of economic and business opportunities; commercial pragmatism, not ideological conviction drives this stream of thinking.

The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM) is by far the most reliable and long-term positive voice on China in the Czech Parliament. The occasional opinion deviations are exclusively brief and policy-unrelated mentions, usually tied to pollution or animal rights abuse.

Civic Democratic Party (ODS), just like TOP 09, forms part of the ideological opposition to China, although its members share a less radical approach. It represents a typical feature of the center-right part of the Czech political spectrum that sees China through the prism of anti-communism. However, in the past time periods, ODS exhibited distinct traits of what could be labeled as ‘commercial pragmatism’.

The Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD) was a leading party of the government that formulated the pro-China U-turn in the Czech foreign policy. The number of positive mentions on China by ČSSD skyrocketed from 2014 to 2017. After comparing the data with the ODS we argue that the ‘pro-China’ and ‘anti-China’ views were adopted on the divisive line of government and opposition, regardless of the governing parties. Pro-China views have become one of the regular topics used by the opposition against the Czech government. The debate on China in the Czech Chamber of Deputies is thus heavily influenced by and linked to Czech internal politics.

Views on China of current prime minister Andrej Babiš seem to be insufficiently pronounced. In the context of clear-cut promoters or critics of China, Babiš seems to have taken a decidedly neutral stance.

While members of the SPD have been surprisingly silent on the issue of China, Pirates have joined those MPs who hold clearly articulated stances critical of China.

The research identified 151 key agenda setters of the parliamentary discourse on China. The debates have produced two unequivocal defendants of a pro-China stance in Bohuslav Sobotka and Vojtěch Filip, leaders of the Social Democratic and Communist parties, respectively. They were followed by others, most notably Social Democrat Jiří Paroubek or Communists like Miroslav Ransdorf or Pavel Kováčik. At the other end of the spectrum stand Miroslav Kalousek, Miroslava Němcová, Zbyněk Stanjura or Jan Zahradník from the ODS, or František Laudát from TOP 09.

Due to a combination of internal and external developments, the parliamentary debate seems to be returning to where it started after 1989 – to seeing China as a morally bad, authoritarian, dangerous actor whose policies and initiatives need to be opposed, rather than welcomed. The new spike in criticism of China in the Czech Republic, however, does not return the debate to its state in the 1990s as the debate on China has grown more diverse.

The policy paper is available for download here.