Slovakia: Local proxies take charge

Among the global powers, China is a relative latecomer when it comes to public communication of its ideas about international affairs to the Slovak audience. Instances of heightened activity typically concerned situations closely linked to the China’s core interests, such as the 2019 protests in Hong Kong against the Beijing proposed extradition law, or the 2020 outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, both issues having a high relevance for the domestic legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

This chapter analyzes Ukraine-focused narratives produced by two types of sources. First source is the Chinese Embassy in Slovakia – its official website, and its Facebook and Twitter accounts. The embassy’s presence on social media is a relatively new phenomenon. Both profiles were created only in February 2020, at a time when China found itself in a position where it needed to salvage its souring public image in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, a failed venture as public opinion polls revealed. The second group of sources includes messaging by Slovak politicians known to sympathize with China.

Importantly, Slovak audiences may consume not only the narratives put forth by Chinese actors located in Slovakia (and their proxies), but also in the neighboring Czech Republic, due to linguistic proximity and general intelligibility of the languages. Hence, media like the Czech edition of the China Radio International (CRI) which primarily targets the Czech audience, may also have an impact in Slovakia.

In the official channels, China has so far not been particularly active in sharing its views on the war in Ukraine. In the examined period, almost no original content attributable to the embassy staff was found. The embassy’s activity was limited mostly to reposting content produced by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, other Chinese institutions, and their representatives. First social media posts regarding the war started appearing only in mid-March, almost three weeks after the war started.

In one of the first posts, the embassy retweeted the post of the Chinese embassy in Poland (itself retweeting People’s Daily) about Chinese aid to Ukraine.102 The embassy also shared the readout of the video call between Xi Jinping and Joe Biden. It highlighted a quote by Xi Jinping: “Countries should not come to the point of meeting on the battlefield. Conflict and confrontation are not in anyone’s interest. Peace and security are what the international community should treasure the most.”

The topic of refugees has also featured in the official communication. Two types of comments were made. Concerning the Chinese nationals fleeing Ukraine via Slovakia and other neighboring countries, the embassy shared the comments of Wang Wenbin, the Spokesperson of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, expressing gratitude for the support provided in extracting the stranded Chinese nationals. The only reflection of the war on the embassy’s website also concerned the fleeing Chinese citizens, albeit limited to practical information for the fleeing Chinese.

It is apparent, that in Slovakia the embassy focuses mostly on positive communication. The necessity of diplomatic resolution of the conflict while stressing its own provision of aid to alleviate the impact of the war is highlighted. Negative comments, such as attributing the blame for the war to the West and NATO expansion, are largely suppressed.

One of the most vocal proxies in Slovakia is Ľuboš Blaha, a Member of the Parliament from the Smer-SD, a populist leftist and nationalist party. Shortly after the war started, Blaha posted on Facebook a theory on bioweapon labs in Ukraine purportedly established by the US. The post was liked by over 9,000 Facebook users, shared over 1,400 times, and received some 1,100 mostly supportive comments. The post was also shared across various Slovak and Czech Facebook pages that typically cater to nationalist, pro-Russian, and anti-system audiences.

On the opposite side of the political spectrum, far-right politicians also expressed sympathies to China amidst the war in Ukraine. Marián Ďuriš, a member of the Presidium and a self-styled foreign policy expert of the far-right Republika Party, highlighted on his Facebook page the nature of the China-Russia partnership that can potentially help Russia to avoid Western sanctions. However, in Ďuriš’ view, China aiding Russia to avoid the sanctions is not a problematic behavior in and of itself, but merely a cause of weakening international position of the EU and the US. He further concludes that the Slovak government, which supports sanctioning Russia, is not acting in the interest of Slovak citizens but rather in the interest of foreign powers.

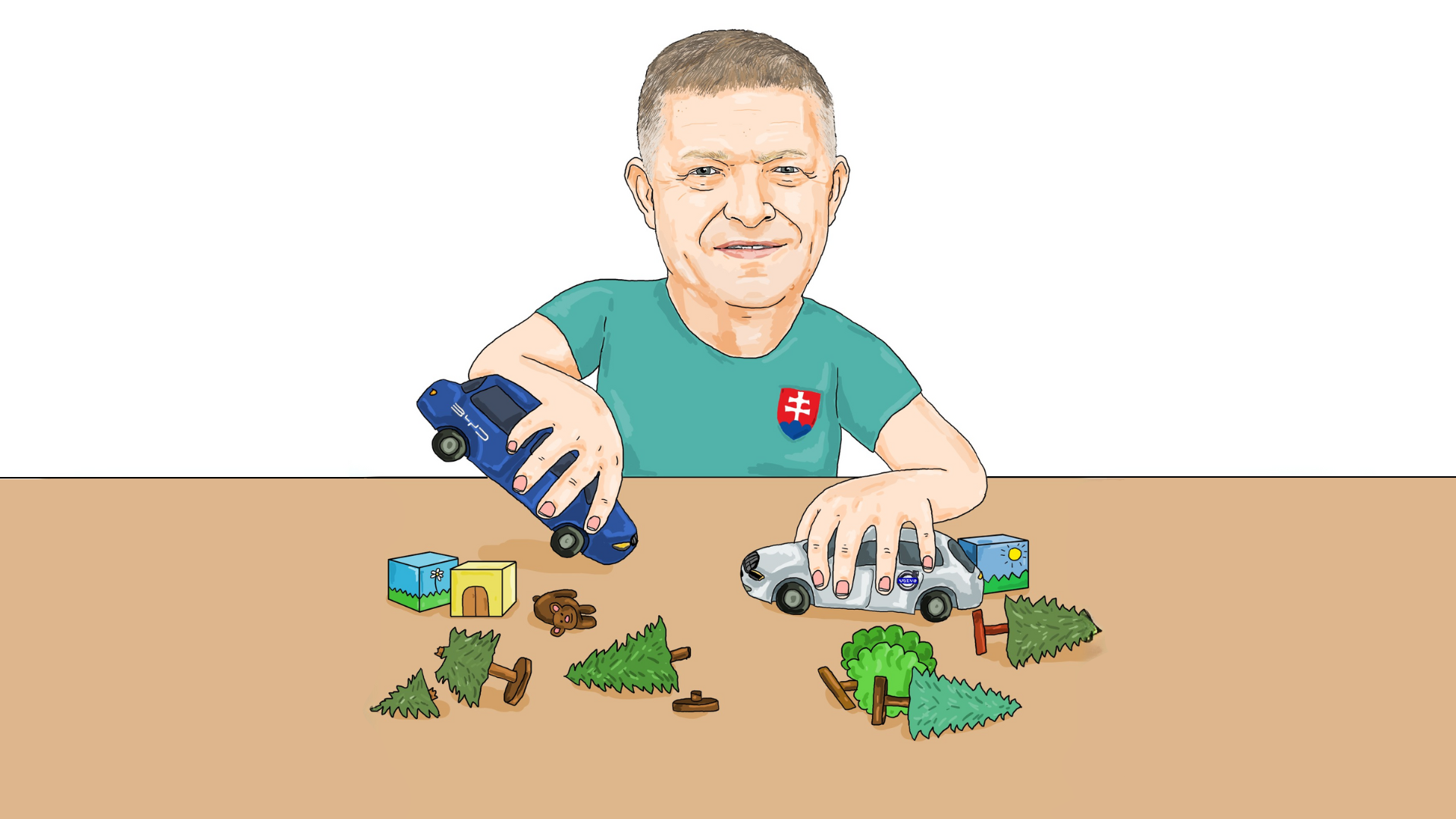

In Slovakia, the official Chinese channels are not particularly active when it comes to spreading propaganda on the war in Ukraine. Chinese messages focused mostly on positive communication, highlighting China’s claimed commitment to peace and diplomatic resolution of the conflict. This is largely in line with the previous instances of an embassy’s restrained style of communication, making the Chinese Embassy in Slovakia an exception in the surging ‘wolf warrior’ approach seen elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe. Vitriolic messaging has been typically taken over by the local proxies. Both ideological and pragmatic reasons can help to explain this phenomenon. Proxies typically come from amongst both far-right and far-left political extremes, to whom, on one hand, China allures ideologically. Thus promoting Chinese viewpoints helps Slovak proxies to assuage the demand of their electorates for anti-systemic messaging.