The article was originally published in our sister portal CHOICE (China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe).

To improve the transparency of Chinese companies, the EU needs to change how it approaches beneficial ownership registration under the block’s Anti Money Laundering (AML) rules.

A large part of the discussions surrounding security risks posed by Huawei’s involvement in 5G networks and other critical infrastructure has revolved around one question: Who owns Huawei?

Huawei itself insists that it is owned by its employees, with its founder Ren Zhenfei holding only a paltry minority stake of 1.14%. However, many remain understandably skeptical of this claim.

A 2019 working paper by professors Christopher Balding and Donald Clarke claimed that what Huawei calls “employee share ownership” is merely a profit distribution scheme. The paper then goes on to explain, that the majority shareholder of Huawei is a ‘trade union committee’, which suggests that Huawei is indirectly controlled by the Chinese government.

Since the paper by Balding and Clarke was published, Huawei engaged in a PR blitz to manufacture an image of a transparent company. Meanwhile, Chinese academics like professor Wang Jun of the Chinese University of Political Science and Law have argued against this claim, such as in this translation. The challenge was met in turn with a rebuttal by Balding, available here.

Around the same time as that debate was heating up, half a world away, EU member states were working on adopting laws transposing the so-called 5th AML Directive, a law aiming to improve the regulations on preventing money laundering and financing of terrorism. The AML Directive also holds some relevance in the search for answers to questions about Huawei’s ownership.

Ultimate Owners in the Limelight

One of the obligations set for the member states under the new AML Directive is the creation of public registries of ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs), natural persons who

own or control a company. Typically, this would be a person who, directly or indirectly, owns at least 25% of the company’s shares or can exercise at least 25% of voting rights in the company.

States were already obliged to collect data on UBOs under the previous, 4th AML Directive. This data, however, was available only to a small group of regulators and entities tasked with preventing money laundering and financing terrorism. With the 5th AML Directive, the EU took a turn towards a more transparent regime, as it provides for the creation of public UBO registers, where everyone can check who actually holds ownership interest in companies operating in the EU.

On paper, this may seem like a solution for settling the debate on Huawei’s ownership. However, a reality check from one member state shows that expectation is overly optimistic.

Slovak Experience

First, it must be stated that not all member states have fully transposed the 5th AML Directive thus far. As of June 2020, only 13 member states have opened their UBO registers to the public.

One of the early adopters was Slovakia, a country that has been a pioneer in adopting transparency solutions, especially when it came to curbing the influence of oligarchs.

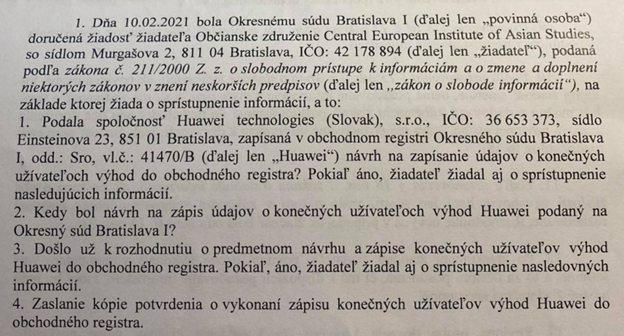

Under Slovak laws, all companies established before November 2018 were obliged to record their UBOs in the Business Registry by the end of 2019. Huawei’s Slovak subsidiary – Huawei Technologies (Slovak), s.r.o. – was established in 2006, and thus had a very clear obligation to register its UBOs.

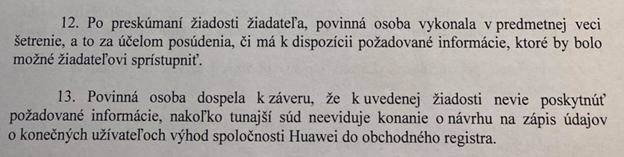

However, to the present day, the Slovak UBO registry does not reflect any information on the identities of Huawei’s UBOs. A response to a freedom of information request filed with the District Court Bratislava I, a local court handling Huawei’s corporate filings, stated that Huawei has yet to file a request to record its UBOs.

The court’s response does not tell us anything about Huawei’s ownership background. However, it indicates that Huawei broke Slovak (and EU) AML laws. While it does not disprove Huawei’s claims about employee ownership, such actions undermine the credibility of Huawei’s statements.

Weak Enforcement

The current UBO transparency regime under the AML laws lacks a strict enforcement mechanism. There is no formalized investigation mechanism to verify the UBO declaration. This makes it difficult to challenge the declaration made by any company in cases where there are doubts about the veracity of the submitted data.

Under Slovak law, failing to declare data on a company’s UBOs, or declaring false data, is punishable by a fine of a mere €3310. This is a small price to pay for a large multinational corporation to maintain its ownership secrecy.

To achieve bigger corporate transparency of Chinese companies operating in the EU, we need to rethink the process of how UBO declarations are made. Slovakia’s fight against shell corporation offers an example of how to achieve this.

Towards a Radical Transparency Regime

Aside from the regular UBO register under AML laws, Slovakia also has the ‘Register of Public Sector Partners’. Generally, every company which is to be paid over €100,000 from the public purse, must declare its UBOs in this registry. Compared to the AML obligation, here the process of declaring UBOs significantly differs in four crucial aspects.

The obliged company cannot declare UBOs on its own. Instead, the declaration is made after UBO verification by an independent third party (auditor, notary public, bank, or an attorney-at-law). This already significantly reduces the risk that the false data would be registered. In 2019, a court even fined a law firm that verified a company’s UBOs despite conflicting interests. The fine amounted to €160,000. The verification document prepared by the independent third party, which is publicly available, contains not only the names of the UBOs, but also a description of the entire ownership structure based on which the UBO identification was made.

Secondarily, anyone can challenge the UBO declaration, leading to an investigation by the court. This option has been regularly employed by anti-corruption NGOs and investigative journalists which regularly challenge UBO declarations of companies with suspected hidden ownership. This has forced several powerful oligarchs to make their control of companies, which significantly benefited from public tenders, fully public.

Additionally, once a court investigation is opened, the challenged company faces a reversed burden of proof. This means, that neither the court nor the activist must prove that the UBO declaration is false. Rather the challenged company itself has to prove that the declared UBO data is true. While the reversed burden of proof does not cause much trouble to companies that do not bypass the law, it poses a serious disadvantage for dishonest businesses.

Finally, if the court finds that the UBO declaration was false (regardless of intention), the company will be expulsed from the register and blocked from re-registering for the next two years. This has serious ramifications for the company, as it cannot engage in activities for which registration in the register is necessary, especially participating in public tenders.

While originally the law was devised to cover only entities passing a certain threshold of income from public funds, over time, the law has been evolving to include also en bloc inclusions of companies operating on markets where bigger ownership transparency is deemed necessary. These block inclusions were recently extended to health insurance companies, and attempts have been made to extend the law to the media sector as well.

To prevent security risks posed by investments of opaque companies into sensitive sectors, the law’s scope should be broadened to include any companies operating telecommunications networks and other critical infrastructure or engaging in research of dual-use technologies. This could already deter companies from entering these sensitive sectors if they do not want to uncover their ownership structures.

‘Weaponizing transparency’ is an elegant solution as it is a country-agnostic (thus lowering the risk of discrimination accusations) and addresses risks posed not only by companies linked to foreign authoritarian regimes but to domestic kleptocrats and oligarchs as well. As the EU’s current AML regime cannot achieve a comparable level of transparency, EU legislators should take note of the innovations developed in Slovakia and incorporate them into the next AML directive.

This would not be a panacea, and other tools still need to be developed to limit the CCP influence in corporations via grass-root party cells or Chinese intelligence legislation. Still, revamping how companies in the EU declare their UBOs would shed much-needed light on the corporate structures of Chinese businesses operating in the EU.

As US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis noted over 100 years ago, “sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.”

Image source: Wikimedia Commons